When you correct your mind everything else will fall into place.

Lao Tzu.

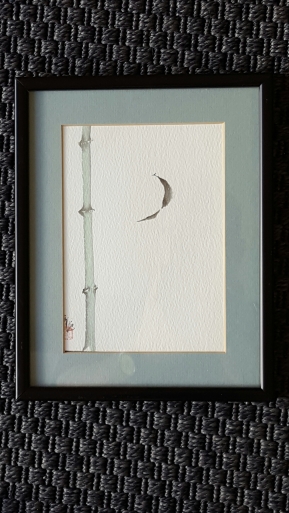

A few years ago I went through a difficult period with stress and depression. At this time my partner commissioned this brush painting for me. It shows a bamboo leaf falling, twisting in the air, full of life, while at the same time it is suspended in a single moment. A moment in which anything is possible, a moment that is full of possibility and in which nothing can be taken for granted.

It serves as a reminder that nothing lasts, that everything is transient, and that I need to do my best to stay in the present moment, open to new experiences and doing whatever I can to remain open to whatever opportunities and options come my way. It also reminds me that making predictions can be fraught with danger, after all a dragon might just fly down and eat the leaf.

This is also one of the reasons why I like rainbows, those fleeting, numinous phenomena that only exist in the eye of the beholder. A momentary experience of physics in action, something that is best when it is just experienced and enjoyed, not analysed.

This is what mindfulness is all about. The constant coming back to the present moment when we get lost in thoughts about the past, or perhaps find ourselves agonising over the future. Taking the time to be right here, right now, staying involved in our lives as they unfold. Actually sitting down to watch our children perform in their school play rather than missing the performance all together by being too concerned with making a recording of their performance to post online.

Caught in a single moment of time.

When we are not present in the moment then there is room for cognitive dissonance to arise, the strange sensation of dislocation that arises when our thoughts and feelings are out of keeping with each other. An unpleasant experience that causes us subjective feelings of distress which are usually out of all proportion to the situation in which we find ourselves.

This is a state of tension and an unpleasant emotional condition that comes to the fore when our experience of the world is out of keeping with our expectations and sense of reality. This makes it far too easy for us to misinterpret not only how we are feeling, what we are doing, or even how we are coping, but also the motives and behaviour of others.

This state of being usually arises when our lived experience is out of sync with the stories and myths that we tell ourselves about our lives and our role within them. These are the stories that form the core of our personal culture. This is a significant cause of dissatisfaction with life.

In light of such experiences any change can feel “wrong”, not because there is anything inherently wrong with what is happening but purely because we are not used to it. It does not fit within our current narrative and so takes us too far out of our comfort zone. So we no longer dare to try new things, we tell ourselves “I couldn’t do that,” “It is not the sort of thing that I do,” “I am not that sort of person.”

This uncomfortable emotional state arises in response to the times when our habitual and semi automatic thinking processes are no longer adequate to allow us to adapt to the changing circumstances of our lives. This then activates our internal threat detection systems, the fight and flight responses that have kept humans alive in times of danger for many millions of years. When this happens it is very easy for us to overreact to our lived experience. So we end up in a state of mind where what is in reality only a slight discomfort can be experienced as major distress. In PTSD this phenomenon causes the sufferer to react to minor environmental triggers as though the original traumatic event was still happening, and causing them further trauma from re-experiencing the original events as though for the first time.

These exaggerated responses to relatively trivial triggers shut down our ability to adapt and change our behaviours by reducing our ability to think in times of stress. thinking as a process takes time – something that matters when our life is in danger, as we may need to react to a threatening situation immediately and not spend time pondering our options if we are to survive. For this reason we often find ourselves reacting to current events with learned responses from our past.

Our mind can react to past events, or to fears about our future in much the same way, we detect a degree of cognitive dissonance that generates a response that is based more in survival mode that out of rational thought. If we can remain mindful and return to the present we are then in a position to do what is best right now, and not allow other concerns about past or future mental states or events to influence our current predicament and the solutions that we generate to resolve it

The path to happiness and contentment requires that we are able to calm our mind and thoughts; to be able to do this we need to become more attuned to our feelings and perceptions of the world and events around us. Then we can respond from the current situation and its particular needs rather than reacting out of the habitual, automated beliefs and emotional responses that we have garnered along the way. These habits can be helpful in many ways, and can free up mental energy for the more important areas of our lives and not lead us to waste this energy on the mundane parts of our lives. This is one of the reasons why well-known figures such as Steve Jobs or President Obama wear a limited wardrobe, and tend to eat the same things; they then have more energy free so that they can apply it to the more important decisions and choices in their, and our, worlds.

Being in the moment is not about being trapped in amber like some prehistoric mosquito. Instead it is about being aware, moment by moment, of how we are responding to the events in our lives as they happens, permitting us to maximise the joy and minimise the distress that arises in response to the vicissitudes of life. It enables us to take life much more in our stride, giving us greater control over how we choose to see our world, allowing us to create a greater sense of agency and control over ourselves and the world around us. Not continuing to respond to the ups and downs of our lives in habitual ways as if we are reacting because we hear what we expect to hear, rather than listening to what is actually said, and then, and only then, responding as needed.

Practicing these skills can help to improve our daily lives, and many people find that developing a regular, daily mindfulness practice of some kind, whether it be formal mediation, being in nature, or perhaps practicing a much-loved hobby, can help us to live less from habit and with greater freedom. Mindfulness is a skill that can be learnt. Much like learning to drive a car, the more practice we get the more automatic it can become, and then it is there when we need it most.

To quote Thich Nhat Hanh;

It is only in an active and demanding situation that mindfulness really becomes a challenge.

And it is at times like these when we need it most.

Sandy

vajrablue.com

19/06/2016 at 3:26 PM

This is an excellent piece. Well written and very insightful. I am new to mindfulness and this piece was invaluable to me. Many thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

19/06/2016 at 6:08 PM

Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike

19/06/2016 at 3:49 PM

Great post

LikeLiked by 1 person

19/06/2016 at 6:08 PM

Thanks for your comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

22/06/2016 at 10:45 PM

what a nice post. I can relate to this. I find myself distressed and out of place when I’m not mindful. Helpful post.

LikeLike

01/07/2016 at 6:01 AM

Couldn’t have been said at a better time!!! Thank you!

LikeLike